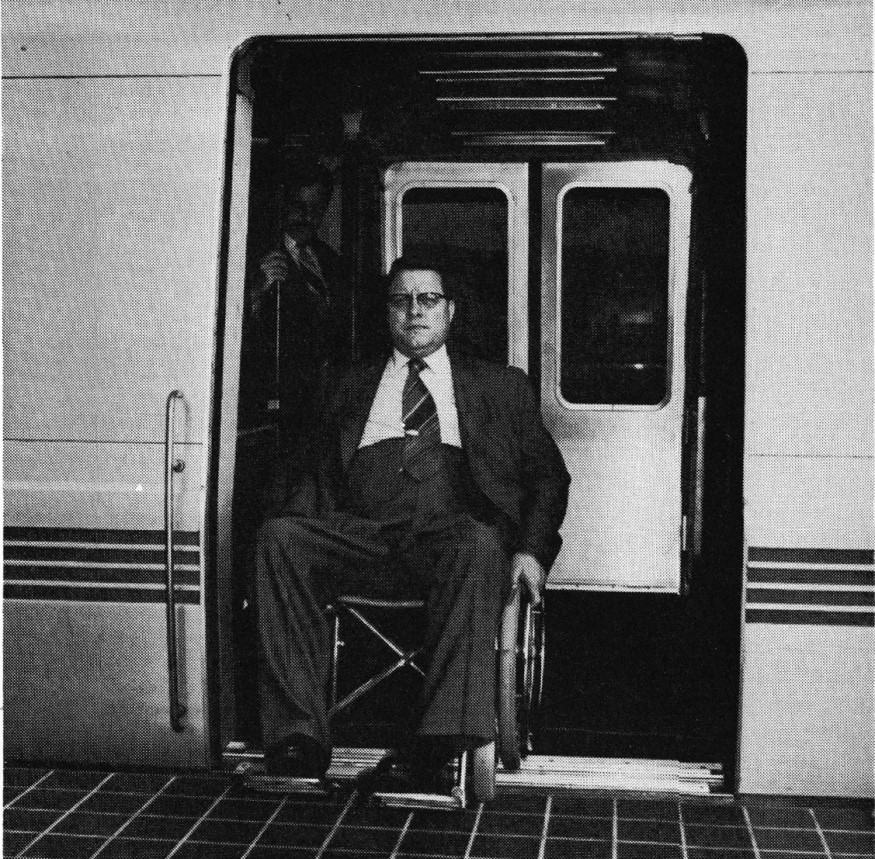

“There is a special personal pride in being the first handicapped person in a wheelchair to use a subway train, and to represent all handicapped travelers who will use the BART system in years to come. I’ll never forget that sense of freedom I experienced as I boarded the BART train.”

– Harold Willson, quoted in “Accent on Living,” Spring 1973

Photo courtesy of Kaiser Permanente Heritage Resources.

When Harold Willson was 21 years old, his life forever changed.

The West Virginia native dropped out of university when his funds ran out and took up work as a coal miner. On a regular day in February 1948, about two years after he began working in the mines, Willson was caught in a slate fall. He suffered severe spinal damage, broken ribs, and a broken back.

Willson’s tragic accident spurred a lifetime of advocacy, the effects of which continue to impact the freedom and mobility of transit riders across the nation. After Willson, “Never again would skeptics be able to argue that trains could not be made wheelchair accessible,” according to the book “The Disability Rights Movement” by Doriz Zames Fleischer and Frieda Zames. Thanks to Willson’s efforts, BART would become the first 100-percent accessible public transit system in the nation.

Four months after his accident, Willson was transferred by train to the Kaiser Foundation Rehabilitation Center in Vallejo. It was a felicitous move, one that would forever alter the course of his life and public transit as a whole. In his two years at the facility, Willson underwent intensive physical therapy and multiple surgeries. Doctors told the young man he would be a wheelchair user for the rest of his life.

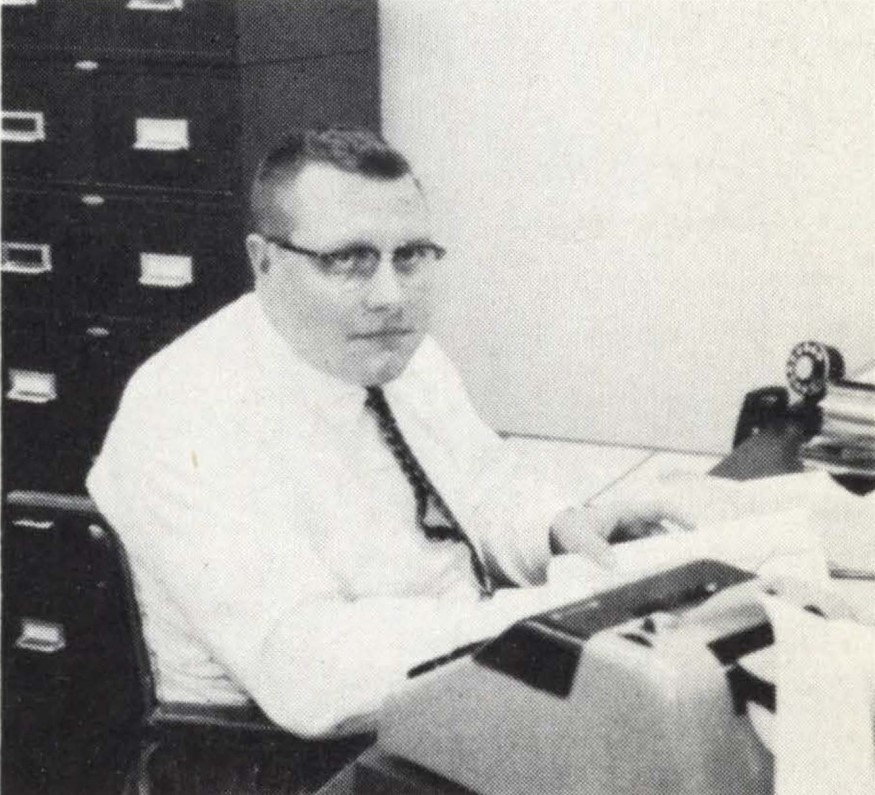

In 1950, Willson joined Bank of America and met his wife, Patricia Leister, who was a member of the nursing staff that treated him. Six years later, he completed a degree in business administration from Golden Gate College, and a year after that, the Kaiser Foundation Medical Care Program hired him as an accountant. Willson would go on to hold a variety of positions at Kaiser Permanente throughout his life. He’d retire as the senior financial analyst for the Kaiser Foundation Health Plan in 1977.

“Kaiser Permanente is fortunate to have passionate and influential employees like Harold Willson, whose remarkable success advocating for historically overlooked needs of people with disabilities led to substantially improved conditions,” said Cuong Le, historian for the nonprofit health care provider.

During the years that Willson lived in the Bay Area, residents were aflutter with news of a soon-to-be-constructed rapid transit system that would connect the region. But the tenor of excitement shifted for Willson when he learned the system, called the San Francisco Bay Area Rapid Transit District, or BART for short, would not be accessible for people with disabilities. Four percent of the Bay Area population at the time had severely limited mobility, meaning the BART system would exclude them from its ridership.

“When the system was built in the 60s, the elevators weren’t part of the consideration,” said Bob Franklin, BART’s Director of Customer Access and Accessibility. “They were completely an afterthought.”

Photo courtesy of Kaiser Permanente Heritage Resources.

Willson reached out to BART and offered his services as a “volunteer consultant” to the BART Board starting in 1964. He had a unique approach to advocacy, according to the people who knew and worked with him. A.E. Wolf, the General Superintendent of Transportation for BART, commended Willson’s amenable style in particular.

“His suggestion was novel for rapid transit, no one had tried it,” A.E. Wolf, the General Superintendent of Transportation for BART, is quoted as saying in the Spring 1973 issue of “Accent on Living,” which Kaiser Permanente keeps in its archives. “It posed all kinds of problems; cost was significant. Our staff, including myself, was hardly enthusiastic.”

“But, he did not threaten, nor picket, nor sulk, nor lose patience,” Wolf continued. “Instead, he was professional, pleasant, firm and persistent. As a result, he won the support of each of our board members while maintaining a friendly relationship with our staff.”

Willson’s approach was to “sell” the idea for an accessible BART system by contacting people one by one and having individual conversations with them, slowly winning them over to his cause.

“You could be a pioneer in being the first major public transportation system to be accessible to the handicapped,” Willson told the BART Board and staff as early as 1963, according to Michael Healy’s “BART: The Dramatic History of the Bay Area Rapid Transit System.”

Willson’s methods worked. In 1968, the BART Board requested $7 million from the California legislature to include accessible elevators in its plans. The figure was later revised to $10 million. But Willson’s effort did not stop there. Willson and BART continued to lobby Sacramento until $150 million in additional funding for wheelchair accessibility was allocated to BART in March 1969. It would be more than two decades later that the Americans with Disabilities Act was signed into law, which would set a legal precedent for accessibility rights and accommodations throughout the nation.

Among the accommodations the funding secured were elevators at every station, telephones in elevators and stations that were accessible by wheelchair users, special service gates and handrails, Braille symbols on elevator door casings, loudspeaker directions for the visually impaired, closed-circuit television where needed, and level boarding between the platform and train. In the years since Willson’s advocacy, BART has added even more accessible features to the system, which you can read about on bart.gov/guide/accessibility.

After BART was built, Willson would go on to continue advocating for accessibility. In 1971, Willson and Wilmot R. McCutchen, Chief of Design for BART, testified before a special U.S. Senate Committee on Aging, which served as “an important precursor to raising public consciousness of the issue of disabled access,” according to Healy’s “BART” book. A robust disability rights and independent living movement would emerge in the years that followed.

Willson died in the Bay Area in 1994. His legacy continues to reverberate. After BART, the newly built transit systems WMATA and MARTA also made their systems accessible, setting a new precedent for future generations of public transit.

“All of this is possible because one man had a bright shiny dream, and he made it come true,” Wolf is quoted as saying in a 2008 issue of “Diversity Journal.”

Denise Figueroa, the Executive Director of the Independent Living Center of the Hudson Valley and a longtime transit advocate, noted that transit has “come a very long way in terms of accessibility” from the 1950s and 1960s.

“In those days, when Willson first started out, there wasn’t an expectation of accessibility,” she said by phone. “Over the years, what has changed is that the public expects transit to be accessible – even non-disabled people.”

Figueroa said the mentality of transit systems was often, “It’s not my problem.” She said agencies would routinely cite cost as the prohibiting factor.

“The argument was always: It’s too expensive,” she said. That changed with the passage of the Americans with Disabilities Act (1990), as well as Section 504 of the Rehabilitation Act (1973), which requires public entities that receive federal funding to ensure that people with disabilities are not discriminated against, nor denied goods or services.

Today, BART continues to bolster its efforts to make the system accessible for all riders. The transit agency hosts a monthly BART Accessibility Task Force on the fourth Thursday of each month, where the public can voice concerns, ask questions, and provide input. BART, which is ADA accessible by law, also encourages passengers to make a Reasonable Modification Request if their needs are not being met by the system.

According to Bob Franklin, the Customer Access and Accessibility Department Manager, when transit systems are accessible to all, everybody wins.

“It’s a federal law now that we’re accessible to everyone,” Franklin said. “And when we design it that way, everyone benefits. The more universally we can design something, the better it will be.”